This Canada Day we look inward at the way we understand national history of racism, and ask how public historians can change our society for the better.

This Canada Day comes at one of the most perilous moments in this nation’s history. The jubilant parades, firework shows, and breathless round-the-clock CBC coverage have been tempered by the ongoing pandemic, and given way to virtual gatherings and subdued get-togethers within our COVID-bubbles. It’s also raining here in Vancouver, which has put an additional damper on things.

However much of the news coverage over the past month has not centered on the pandemic, but the collective explosion of rage in the United States following the murder of George Floyd by officers of the Minneapolis Police Department. As hundreds of thousands have taken to the streets in cities and towns across the US to demonstrate against police brutality and systemic anti-black racism, they’ve demanded that American society reckon with the racist demons of its past.

Dozens of statues of Confederate generals and figures like Christopher Columbus have been torn down by protesters, once again bringing the debate on memory and public history to the fore.

As is Canadian tradition, events to the south have made Canadians ferociously debate the same questions. What role does racism play in the way we remember our past, and how have racist systems and attitudes forged decades ago continued to shape the country we live in today? Why do so many people believe statues of John A. Macdonald, the Father of Confederation, need to be torn down?

There is no better time to ask these questions than Canada Day, since the day honours a country that has been cruel, unjust, and violent to hundreds of thousands of people holding Canadian citizenship today. When we celebrate, we should never forget that for many First Nations peoples, it’s a day as bitter as May 15–Nakbha Day–is for Palestinians.

Here we’ll ponder how the example of America’s racist past has helped us airbrush away much of our nation’s own sins, and ask what role public historians can play in shaping the popular narrative of Canadian history.

Looking in the American Mirror

When it comes to racism and systemic inequality, many Canadians have a smug habit of looking to our neighbours south of the border and saying ‘Well at least we aren’t as bad as them.’

We often see the yawning gap between America as advertised and America as lived reality as a particularly American attribute. How could almost all of America’s Founding Fathers own slaves, yet begin the Declaration of Independence with the words “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

Indeed, when pressed, most Canadians would say our nation lives up to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence better than the Americans do themselves.

That’s because popular attitudes about racism and inequality in this country are mostly formulated around historical episodes that directly contrast our nation with theirs. The timeless Heritage Minutes provide some examples.

Instead of slavery, we had Black Loyalists like Richard Pierpoint and the Underground Railroad.

Instead of the Massacre at Wounded Knee, we had Mohawk Chief John Norton and his Grand River warriors holding off American invaders at the Battle of Queenston Heights, and trustworthy Mounties offering sanctuary to Indigenous people fleeing America.

Instead of civil war or revolution, we had John A. Macdonald and George Etienne Cartier using vision and diplomacy to bring English and French Canada together as equal partners in a new nation.

Instead of lynchings, Jim Crow laws, and police dogs and firehoses trained on peaceful demonstrators, we have Viola Desmond peacefully fighting segregation at the Supreme Court, 20 years before the CIvil Rights Act was passed in the United States.

This is not to take a shot at Heritage Minutes–which I love very dearly–and many of them portray clear injustices and racism in Canada. But it is difficult to watch them and not have the thought at the back of your mind ‘yes that was bad, but what was happening down south was so much worse.’

I admit to getting this feeling all the time when comparing our two histories. When visiting Washington state, I learned of the Governor Isaac Stevens, who waged a ruthless and brutal war on the Yakama people in 1855-56, putting a bounty on Indigenous scalps, and even (perhaps apocryphally) watched a man be scalped in his own office.

It’s hard to think of parallel state sanctioned racialized savagery in British Columbia’s history, which was governed at the time by James Douglas, who was half-black.

It’s far too easy to fall back on this defense mechanism when writing about our own history.

These narratives help us forget that towering figures in Canadian history like John Graves Simcoe and James McGill owned slaves, and slavery was widely practiced in New France for centuries. We forget how in 1862 the colonial government of BC allowed, and even encouraged, a smallpox epidemic to spread up the west coast, killing an estimated 30,000 First Nations people, some 60% of the population.

The reality is that our nation too, was built on racism, organized violence, and theft on a world-historic scale. When we use America’s history as an excuse to ignore our own, we do harm to those across this country who are still subjected to the racialized inequalities that built this country.

When premiers and RCMP commissioners deny systemic racism exists in this country, it prevents us from the kind of introspection that might lead to meaningful redress of past wrongs.

Canadian Dream vs Canadian Reality

We hear so much about America not living up to its promise, but how well does Canada pass the same test?

In the typically Canadian way, Canada’s founding principles are more moderate than America’s, merely promising “Peace, Order, and Good Government.” On the first count, we can concede Canada is not a particularly war-like country when compared to most of her peers. As for order, Canada hasn’t experienced any revolutions, with the exception of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution (though calling it ‘quiet’ kind of helps my case). ‘Good government’ depends on one’s political sympathies. There’s nothing quite so galling there as slaveowners claiming all men have the inalienable right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

But what did Sir John A say about liberty?

“We have a constitution now under which all British subjects are in a position of absolute equality, having equal rights of every kind – of language, of religion, of property and of person. There is no paramount race in this country; we are all British subjects and those who are not English are none the less British subjects on that account.”

This claim clearly does not stand up to scrutiny.

When Prime Minister oversaw a genocide of the Plains First Nations, who were experiencing brutal famine after the buffalo that they relied on had been hunted almost to extinction. Macdonald’s policy was to deliberately starve the Indigenous to break their resistance to move onto reserves.

“I have reason to believe that the agents as a whole … are doing all they can, by refusing food until the Indians are on the verge of starvation, to reduce the expense,” he told the House of Commons in 1882.

In 1883 his government began the cultural genocide of the First Nations too by establishing the residential school system. His reasoning?

Indigenous people were forced to get permission from the Indian Agent to leave their reserves, and were denied the right to vote until 1960. Macdonald’s “Equality of language, religion, property and person” was a cruel joke to the First Nations, and left wounds that have never healed.

The Immigrant Experience

While the First Nations were obviously exempted from Canada’s claims to universal equality, many different immigrant groups were also subjected to various forms of discrimination, and continue to be so today.

In 1905 Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, author of Canada’s first immigration boom and promoter of the 20th Century as the ‘Canadian Century,’ gave a speech to a jubilant crowd in Edmonton to welcome the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan into Confederation.

His soaring rhetoric is inspiring.

“Let me say to one and all, above all those newly our fellow countrymen, that the Dominion of Canada is in one respect like the Kingdom of Heaven: those who come at the eleventh hour will receive the same treatment as those who have been in the field for a long time.”

He continued:

“We want to share with them our lands, our laws, our civilization. Let them be British subjects, let them take their share in the life of this country, whether it be municipal, provincial or national. Let them be electors as well as citizens. We do not want nor wish that any individual should forget the land of his origin.”

“Let them look to the past, but let them still more look to the future. Let them look to the land of their ancestors, but let them look also to the land of their children. Let them become Canadians, British subjects and give their heart, their soul, their energy and all their power to Canada, to its institutions, to its King, who like his illustrious mother, is a model constitutional sovereign.”

These benevolent words would ring hollow to many Canadians.

Two years later, speeches given at a meeting of the Asiatic Exclusion League in Vancouver whipped a mob into a frenzy, and 6,000 whites rampaged through the Chinese and Japanese neighbourhoods, beating people up and looting shops.

Anti-Asian racism has deep roots in British Columbia, and the province used policies like the head tax to deter Chinese immigration. Finally in 1923 Chinese immigration was banned entirely.

The first drug law in Canada followed soon after. It was a ban on opium, because of a “highly racialized drug panic” that spread rumours of white women being lured into Chinese opium dens. It was “extraordinarily severe drug legislation including six-month sentences for possession.” Naturally Chinese-Canadians were almost exclusively “targeted by enforcement officials,” though people of many backgrounds used the drug. It was the first instance of a drug law being used to criminalize the behaviour of marginalized communities. It would not be the last.

The SS Komagata Maru, a ship of Indian immigrants, was barred from entering Canada in 1914, as politicians and most of the popular press argued this was “a white man’s country.” It’s easy to forget that up to the Second World War, this was more or less the most widely held view in Canada.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/LE3Y6KTNHJDN3B2P7IXRKFRUEY)

During World War II, Japanese Canadians, the Nikkei, were interned and their property expropriated. This was mostly done on racial grounds, since no sane military strategist genuinely believed the Nikkei would act as a fifth column for Imperial Japan.

Sergeant Masumi Mitsui of Port Coquitlam was one of 200 Nikkei who had fought for Canada in the First World War. He was awarded the Military Medal for his valour at the Battle of Hill 70, when he retrieved a machine gun from its dead operators and brought it back into action, leading his all-Nikkei platoon to repulse repeated German assaults. 30 of his 35 men were killed in the engagement.

After the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941 he wrote the Minister of National Defence on behalf of Japanese-Canadian veterans pledging “their unflinching loyalty to Canada as they did in the last war.” When the internment orders came he went to the registration office and flung his medals on the official’s desk. “I served my country,” he said. “You’ve taken everything from me. What are the good of my medals?”

The grateful nation rewarded his sacrifice by sending him to an internment camp in Greenwood, British Columbia.

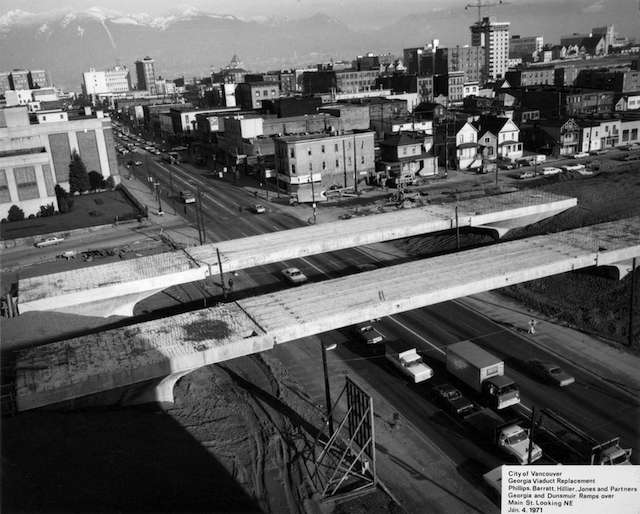

Blatantly racist official policies continued until the fairly recent past, and manifested themselves in a variety of ways. Hogan’s Alley in Vancouver is one example. It was Vancouver’s black neighbourhood, and home to many black cultural institutions. In 1967 the land was expropriated, and the neighbourhood bulldozed to make way for a highway viaduct. This obviously wouldn’t have been permitted to happen if it were a white neighbourhood, and followed an overtly racist pattern of highway building across North American cities.

A complete catalogue of all the racist outrages committed towards immigrants in Canadian history would be virtually endless. In recent decades as marginalized people have fought against racism, they’ve succeeded in making public displays of white supremacy toxic. Yet we are still daily reminded that these attitudes simmer just below the surface, and continue to shape our culture in conscious and unconscious ways.

The deep and systemic roots of racism in this country, the staggering inter generational cost in lost potential, and the risk of white supremacy resurfacing, all make it paramount that Canadians are forced to reckon with the past. We must understand our history in order to identify those societal institutions and mores that were laid down when saying “Canada is a white man’s country” was an acceptable thing to say. Only then can we overhaul them, or cast them into the dustbin of history.

The Role of Public Historians

Check Back Shortly!